“Mindhunter” is a Netflix series that peels back the layers of criminal psychology in a way that’s both chilling and fascinating. This show gives us a front-row seat to the groundbreaking work of FBI agents Holden Ford and Bill Tench, alongside an academic Dr. Wendy Carr, dive into the minds of America’s most notorious serial killers. If you’re like me, you can’t get enough of true crime dramas, and “Mindhunter” serves it up in spades.

But what hooks me isn’t just the shocking stories or the morbid curiosity; it’s the deep exploration into psychology—the systematic investigation of human behavior and cognitive processes. “Mindhunter” really shines a light on how far we’ve come in understanding those dark corners of our psyche, delving into what drives individuals to commit heinous acts. The agents’ interviews with these criminals aren’t simply shocking tales; they function as case studies from which we can glean insights that help prevent future tragedies.

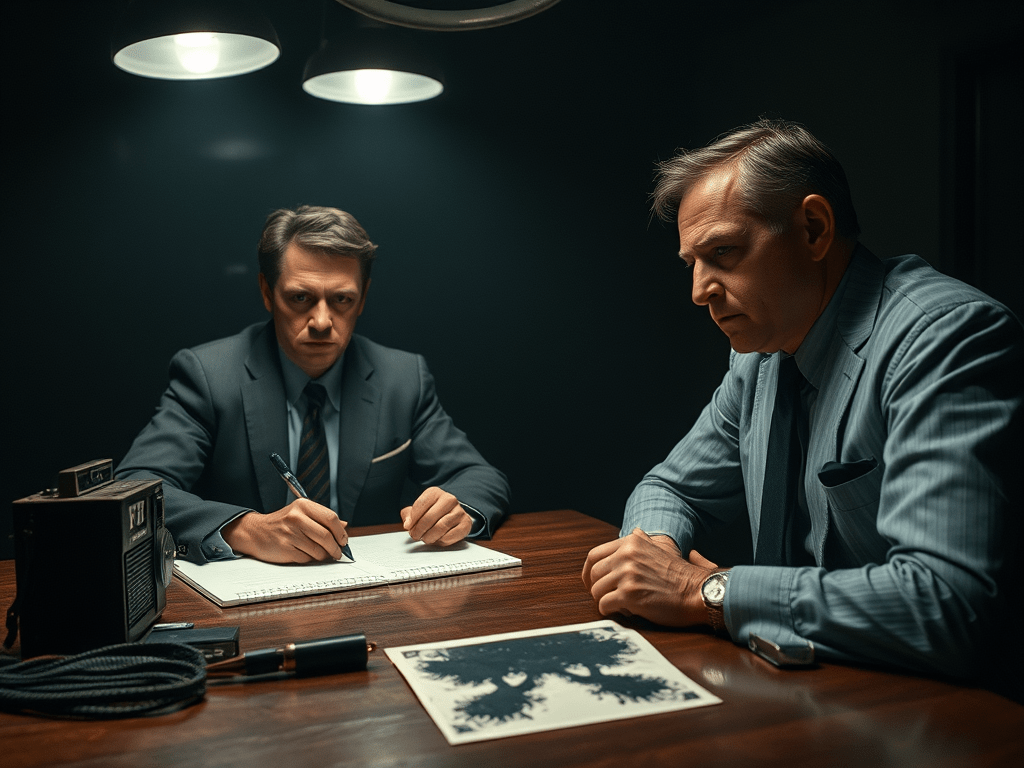

One interesting aspect to note when diving into “Mindhunter” is the absence of two staples in clinical psychology: projective tests and psychoanalysis. How did they enhance their knowledge? How did they get killers to confess? How did they uncover the truth behind the killers’ motives? Not with projective tests! The FBI agents knew that an attentive clinical interview or social development history would suffice. In “Mindhunter,” it was all about returning to basics with clear-cut questions and tangible evidence that reveal what’s really going on in someone’s mind—no ambiguity necessary! Instead of getting lost in ambiguous symbols like Rorschach inkblots, these gritty officers rely on straightforward interview questions that cut right to the chase. It’s all about concrete objects related to their investigations—no beating around the bush here! So where does that leave projective tests and psychoanalysis? They seem to be losing steam lately. Once regarded as essential tools for uncovering hidden thoughts and feelings, their validity has come under scrutiny over time.

Backstage Pass to Our Own Minds

When I was taught to use projective tests in the ’90s, let me tell you, I wasn’t exactly blown away. My master’s degree took two long years—much of which felt like a study in “how to sit quietly and nod while a professor tells us his thrilling army days and karate adventures.” It was like we were in a bizarre mix of therapy training and old-school storytelling. A particularly indulgent professor could waltz into class with the air of authority, skipping any references to actual scientific disciples. He’d weave pseudo-scientific stories that seemingly tied everything back to why drawing a house could unravel your deepest fears.

Projective tests and psychoanalysis are the intersection where the mystical meets the scientific. When therapists ask their patients to doodle something as seemingly innocuous as their childhood home, a random tree, or even a stick figure of Uncle Bob, they’re not merely seeking new décor for their therapy room walls—though who wouldn’t want a gallery of abstract art depicting family dysfunction? Instead, what they’re really doing is embarking on an archaeological dig into the depths of your subconscious mind. Think of projective tests as quirky treasure maps leading directly to the hidden caverns of your psyche, revealing those sneaky and often absurd unconscious thoughts that we all harbor. Freud himself was essentially the original Indiana Jones of psychology—donning his metaphorical fedora and wielding his whip (made perhaps from overly dramatic interpretations), he explored the dark caves of our minds in search of buried treasures while gently reminding us not to lose our sanity along the way. He hypothesized that neglecting these quirky subconscious tidbits could lead to all sorts of delightful disturbances—think peculiar dreams featuring flying cats or awkward slips of speech at utterly inappropriate moments.

I can’t help but chuckle at how my classmates and I spent an absurd amount of time getting “test subjects” to draw pictures of people, houses, and—you guessed it—more people. The tests we did learn about domestically lacked that mainstream buzz: the Rorschach ink-blot test or MMPI were off the syllabus! Instead, we had TAT (Thematic Apperception Test), where you gain deep insight from random pictures—after all, nothing says “let’s explore the psyche” quite like guessing how someone feels about a heavily shadowed tree!

Psychoanalysis: The Ultimate Therapy For Self-Centered Chatterboxes

Humans are self-absorbed creatures. We could set a world record for the most riveting soliloquy about our own lives. Why dive into complex psychoanalytic theories when the root cause of your troubles is more straightforward than your morning coffee order? People just love talking about themselves! Is this where psychoanalysis shines? The patient strolls into a therapist’s office for a weekly session, eager to unload all those fascinating tidbits about me-me-me. Do we really need an archaeological dig into the depths of the human brain? According to the tenets of psychotherapy, the therapist allows the patient to talk for 50 minutes. It’s mainly all about the patient sharing thoughts focused entirely on themselves. If psychoanalysis truly worked wonders, therapists might need to switch careers since their high-paying clients would graduate in no time! But as it stands, that slow progress towards enlightenment means sweet cash flow for the therapist and endless hours of “me-me-me” discussions.

Psychotherapy is expensive and typically not covered by Medicare or Medicaid, making it accessible mainly to those who can afford long sessions filled with personal reflections. After all, who wouldn’t want to spend a significant amount discussing how misunderstood they feel over lunch with a latte? Patients schedule these sessions to explore how special they are—what better way to spend an hour than indulging in the art of introspection? The beauty of ambiguity is that there is no definite end, allowing therapists to bill as long as patients wish to talk about themselves. Easy money! After all, who doesn’t love a good story, especially when it’s all about me-me-me?

Voodoo Science

I applaud Freud’s talent for unearthing rich insights from our psyche, but it’s time for psychology to swap mystique for methodology. The idea of uncovering unconscious thoughts is alluring—like an archaeological dig into our own minds. Who doesn’t want to believe they have hidden gems within their relatively mundane minds? Freud envisioned that our buried feelings could lead to illuminating dreams or even neurotic behaviors. However, the key to self-awareness isn’t just sharing your emotions through word associations or recounting every high school hardship on a couch. For psychology to be respected as a discipline—and not mistaken for a bizarre form of fortune-telling—it should trade its crystal balls for more objective and replicable research methods. Think less “Oh look, I see a bunny!” and more “Let’s gather some solid data here.” By adopting experimental approaches and enhancing statistical analysis, psychology can confidently proclaim, “Hey world! We’re legitimate!”

Citations and Further Reading

AdilYoosuf. (2018). Mindhunter: A gritty insight into criminal psychology. The Artifice. https://the-artifice.com/author/AdilYoosuf/

Fonagy P. (2003). Psychoanalysis today. World Psychiatry. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1525087/ – PMC

Martamaria (2025). Mindhunter – The Psychology of a Masterpiece. Martamaria’s Substack. https://martamariak.substack.com/p/mindhunter-the-psychology-of-a-masterpiece

McLeod, M. (2024). How Projective Tests Are Used to Measure Personality. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/what-is-a-projective-test.html

Norcross, J, Vandenbos, G, & Freedhelm D. (2011). The history of psychotherapy: continuity and change. 2nd ed. American Psychological Association.

Paris, J. (2025). The fall of an icon: psychoanalysis and academic psychiatry. University of Toronto Press.

Leave a comment